Updated: 2023

When the Soviet Union transferred Scud missiles to Egypt before 1973, the missiles were supposed to remain under the control of Soviet personnel. But they ended up in North Korea, which became the most prolific peddler of Scud missiles in the world.

Building upon previous modules, the story of North Korea’s missile program provides a valuable case study in how a country can first acquire basic missile technologies and subsequently master the techniques to develop longer-range missiles. Because other countries have pursued similar proliferation pathways, and in some cases with substantial North Korean assistance, the North Korean case provides important context for understanding why and how many of the international initiatives designed to address missile proliferation emerged and evolved.

Where did North Korea get its missile technology?

President Hosni Mubarak meeting with Kim Il Sung sometime in the 1980s. Mubarak traveled to Pyongyang at least three times, including in 1980, 1983 and 1990. Photo Credit: KCNA

- Defense cooperation between Egypt and North Korea dates back to the 1973 Yom Kippur War. Following the 1973 war, North Korea and Egypt cooperated on reverse engineering a number of Soviet short-range artillery and missile systems.

- In the mid- to late-1970s, Egypt transferred a small number of Soviet-supplied Scud-B missiles to North Korea as part of a cooperative development program. North Korea reverse engineered the missiles.

- During the 1980s, Egypt subsequently imported North Korean Scud-technology (using expertise Egypt helped to cultivate) after a different cooperative effort to develop a 900 km ballistic missile with Argentina and Iraq failed to show results.

How did North Korea’s program evolve?

- North Korea reverse-engineered the Scud missile, making a number of changes to improve its accuracy and extend its range. North Korea tested an improved Scud-B in 1983, followed by a longer-range Scud-C in 1986.

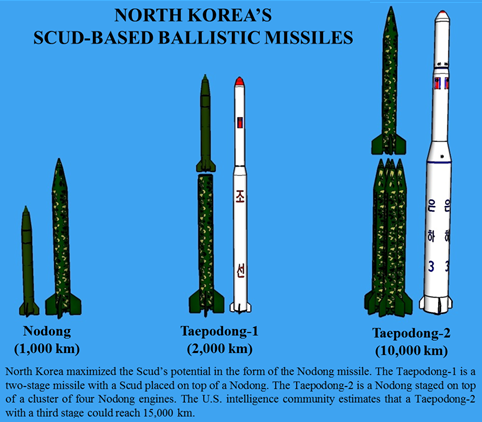

- North Korea maximized the potential of the Scud-based missile in the form of the 1,000 km-range Nodong missile, which it successfully flight tested in May 1993.

- In the 1990s, North Korea displayed mock-ups of Scud-based rockets which used staging and clustering of engines to reach longer ranges than the Nodong.

- The Taepodong-1 is a Scud staged on top of a Nodong. North Korea launched a Taepodong-1 rocket in August 1998.

- The Taepodong-2 is a Nodong staged on top of a cluster of Nodong engines. North Korea launched Taepodong-2 rockets in 2006, 2009, twice in 2012, and once in 2016. Only the December 2012 and 2016 launches were successful. Only the December 2012 launch was successful.

- North Korea’s 2017 launch of the Hwasong-12 intermediate range ballistic missile introduced a new liquid propellant engine that is believed to be a copy of the Soviet-era RD-250. The Hwasong-14, Hwasong-15, and Hwasong-17 ICBMs are all believed to use this engine.

- North Korea has also made progress in the development and testing of solid-fueled engines, which allow missiles to be fueled during manufacturing and offer a quicker state of readiness. North Korea tested its first solid-fueled ICBM, the Hwasong-18, in April 2023.

How did the Scud spread and how has the international community responded?

- North Korea has transferred complete Scud-based ballistic missiles to many countries, including Iran, Pakistan, Syria and the United Arab Emirates.

- North Korea has transferred Scud-based missile technologies to many of these same countries, as well as to countries like Egypt and Libya.

- The threat posed by North Korea’s missile development and the proliferation of its missiles to other countries has motivated the international community to strengthen traditional controls on missile-related technologies and to develop more novel counter-proliferation instruments.

- Members of the voluntary Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) have exchanged technical information and shared “denials” to North Korea to strengthen enforcement of existing limits on the sale of long-range missile technology to North Korea.

- During the 1990s, the Clinton Administration initiated the so-called “Perry Process” to re-engage North Korea diplomatically, including negotiations to eliminate North Korea’s long-range ballistic missile programs in exchange for nutritional assistance and a limited number of space launches. Clinton’s term ended before the parties could reach agreement. The Bush Administration ultimately chose not to continue missile talks.

- Israel reportedly engaged in a covert effort to persuade Pyongyang to end ballistic missile sales to Middle Eastern states in exchange for an unspecified compensation package. [1]

- Following a failed 2002 interdiction of a North Korean ship carrying Scud missiles to Yemen, the Bush Administration created the “Proliferation Security Initiative” to improve collaboration among states seeking to enforce existing counter-proliferation measures.

- Since 2006, the United Nations Security Council has passed four resolutions demanding that North Korea suspend its development of long-range missiles and imposing sanctions on North Korea. These included: UNSCR 1718 (2006), 1874 (2009), 1985 (2011) and 2087 (2013).

- Despite international sanctions, recent reports by the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency and the United Nations Panel of Experts on sanctions against North Korea state that Pyongyang continues to attempt to export ballistic missile technologies and components. [2]

How has North Korea used space launches to further its program?

- There are no significant differences between rockets used as ballistic missiles and rockets used to place satellites in orbit. Rocket programs, including North Korea’s, are often presented as space launch programs in an effort to deflect international suspicions while a country develops and tests technologies for offensive military use.

- North Korea claimed that its rocket launches in 1998, 2009, 2012, and 2016 were intended to place satellites in orbit. (North Korea has not stated the purpose of the 2006 Taepodong-2 launch.) Since 2009, North Korea has conducted these launches from the Sohae Satellite Launch Facility.

- While North Korea no longer disguises its missile tests as launch programs, both its ballistic missile program and space launch program continue to benefit from each other. Intended to place a military reconnaissance satellite into orbit, North Korea’s failed space launch attempt in May 2023 used the Chollima-1 rocket which was based off the Hwasong-17 intercontinental ballistic missile.

- The United States intelligence community has assessed that North Korea has the capability to deploy a warhead on its missiles. [3] This would require North Korea to fashion a reentry vehicle to protect the missile’s warhead from extreme heat when it reenters the earth’s atmosphere.

How do we monitor North Korea’s progress?

- Much of what the United States knows about North Korea’s missile programs comes from defectors who may have overseen or worked in the military complex. [4] This information can be unreliable if not checked against other sources of intelligence, such as overhead satellite images and communications intercepts.

- Missile tests provide important technical information about the state of North Korea’s missile programs. Missile launches are monitored by technical systems such as infrared satellites in orbit and radars on the earth. [5] South Korea recovered debris from the May 2023 failed launch of the Chollima-1 to assess the state of North Korea’s rocket programs. [6]

- Interdictions of illicit shipments to and from North Korea raise questions about the effectiveness of sanctions and provide additional evidence about the state of North Korea’s missile program.

- Open source information can also be a significant source of information. For instance, the Center for Nonproliferation Studies was able to use DPRK propaganda footage, defector accounts and satellite images to locate and characterize North Korea’s site for assembling missile launchers.

Sources:

[1] Aiden Foster-Carter, “Israel and North Korea: Missing the real story,” Asia Times, http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Korea/MD22Dg01.html.

[2] Defense Intelligence Agency, “North Korea Military Power,” January 9, 2021, https://www.dia.mil/News-Features/Articles/Article-View/Article/2812198/defense-intelligence-agency-releases-report-north-korea-military-power/; “United Nations Security Council, Note [Transmitting Final Report of the Panel of Experts Established Pursuant to Security Council Resolution 1874 (2009) Concerning the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea],” March 4, 2021, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3906140?ln=en.

[3] Ankit Panda, “US Intelligence: North Korea’s ICBM Reentry Vehicles Are Likely Good Enough to Hit the Continental US,” The Diplomat, https://thediplomat.com/2017/08/us-intelligence-north-koreas-icbm-reentry-vehicles-are-likely-good-enough-to-hit-the-continental-us/.

[4] “Testimonies of North Korean Defectors,” National Intelligence Service, http://fas.org/irp/world/rok/nis-docs/hwang1.htm.

[5] Craig Covault, “Battered By Explosion Rocket Flew On, North Korean Satellite Likely Blown Off,” America Space, April 15, 2012, http://www.americaspace.com/?p=17476; Luis Martinez, “US Sea Radar Tracking N. Korean Threat,” ABC News, April 11, 2013, http://news.yahoo.com/us-sea-radar-tracking-n-korean-threat-115126485–abc-news-politics.html.

[6] Soo-Hyang Choi and Hyonhee Shin, “South Korea Recovers Part of Rocket Used in North’s Failed Satellite Launch,” Reuters, June 15, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/south-korea-recovers-part-rocket-used-norths-satellite-launch-military-2023-06-16/.

Note: Header Graphic Credit: North Korean Government