1. What is the nuclear triad?

The nuclear triad comprises three kinds of strategic nuclear delivery systems maintained by DoD—bombers, land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs). Although the United States did not set out to build a triad, most analysts believe that having bombers, land-based missiles, and submarines strengthens deterrence. Others argue that the triad is an artifact of the Cold War, and that redundant capabilities are an unnecessary extravagance.

The Nuclear Triad: 1. B-52 nuclear bomber (top), 2. Land-based Minuteman III ICBM (lower right) Source: U.S. Air Force; 3. Trident II SLBMs on Ohio-class ballistic missile submarine (lower left). Source: U.S. Navy.

- Bombers: Prior to the deployment of long-range missiles in the 1960s, bombers were the only nuclear delivery system. Highly vulnerable to anti-aircraft systems, their primary contemporary mission is in signaling nuclear readiness to allies and adversaries for deterrence purposes.

- ICBMs: ICBMs may be fixed and stationed in hardened silos, or be rail or road mobile, and can be launched from within a country’s own territory. If fixed, they are vulnerable to a first strike, but would be unlikely to be successfully intercepted following launch.

- SLBMs: SLBMs are highly invulnerable, as the submarines that carry them are mobile and capable of remaining submerged for lengthy periods of time, during which they are extremely difficult to detect. In the context of the triad, they are perceived as offering an invulnerable second-strike capability.

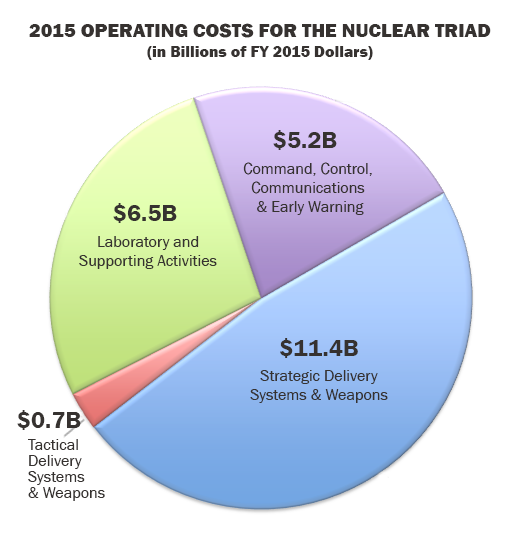

2. What are the annual operating costs of the triad?

The DoD does not maintain a comprehensive budget for the triad, but an authoritative 2015 estimate by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) pegs the cost at around $23.9 billion per year. [1] This figure includes the costs for warheads borne by NNSA, as well as for command, control, communications, and early-warning systems, but excludes any classified costs borne by the intelligence community.

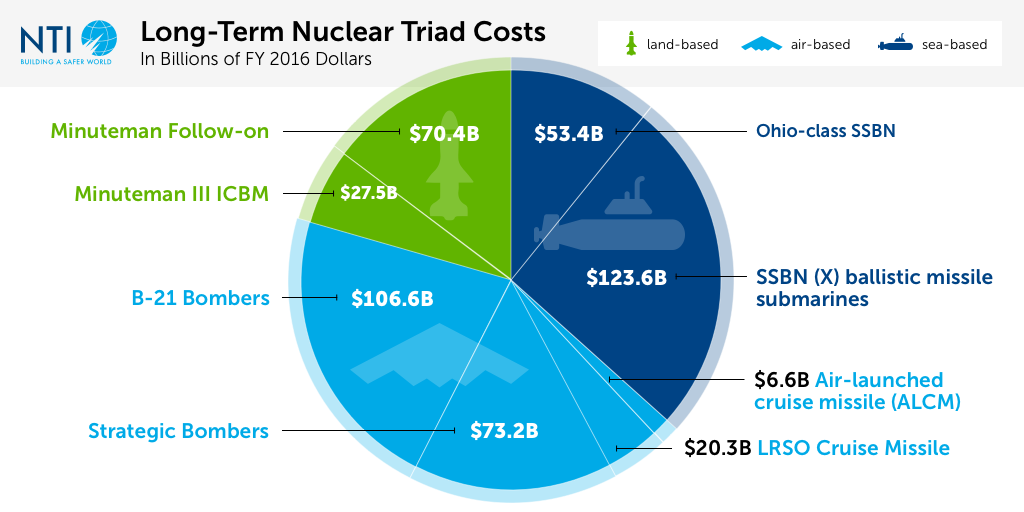

3. What are the long-term costs of maintaining and modernizing the triad’s systems?

The Pentagon has warned that the cost of modernizing the U.S. nuclear deterrent will be challenging. “We’re looking at that big [nuclear] bow wave and wondering how the heck we’re going to pay for it,” said Principle Deputy Under Secretary for Policy Brian McKeon in October 2015. [2]

According to the CBO, over the next ten years the total cost of operating and sustaining U.S. nuclear forces is estimated to be $348 billion. [3] But the dramatic increase in spending known as the “bow wave” will occur in the mid-2020s, beyond the planning horizon for the CBO study. In its January 2016 study the Center for Strategic and International Studies described the bow wave as a self-perpetuating phenomenon that degrades the ability to modernize and maintain the U.S. nuclear arsenal due to funding instability, cost overruns, and inadequate acquisition oversight capacity, to name a few factors that will drive cost increases. [4]

A 2014 analysis by the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies projects that over the next thirty years the total cost of maintaining and updating the triad could reach $1 trillion, with procurement costs for new systems peaking between 2024 and 2029. [5]

DoD is projected to spend an enormous amount of money replacing each leg of the triad with new systems over the next thirty years. The Navy plans to replace its fleet of Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines, which is estimated to cost up to $123 billion (in FY16 dollars). The Air Force currently plans to purchase the new B-21 strategic bomber to supplement the existing fleet of B-52 and B-2 bombers, at a cost of up to $106 billion. [6] In 2015, the Air Force decided to replace its entire fleet of Minuteman ICBMs, which could cost up to $70 billion. [7] (For background on ICBMs and other nuclear delivery systems, see the NTI Delivery Systems Tutorial).

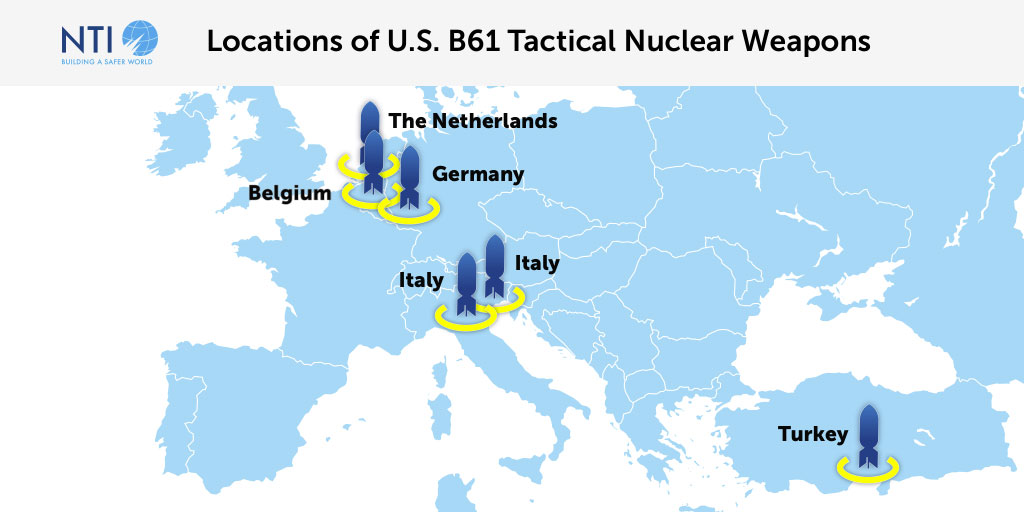

4. What are the costs of keeping tactical nuclear weapons in Europe?

Tactical nuclear weapons, also known as non-strategic nuclear weapons, are weapons designed by the United States and Russia during the Cold War for short-range, limited yield, and battlefield use.

The United States currently deploys around 200 B61 gravity bombs at six bases across five European countries (including Turkey), as part of its commitments to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). [8] These tactical nuclear weapons are part of what is often referred to as NATO’s nuclear umbrella, extending U.S. nuclear deterrence to European allies.

Russia has about 2,000 tactical nuclear weapons. [9] These weapons are held in central storage locations for deployment with ground forces in the event of a military conflict.

The CBO estimates the cost of stationing U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe to be approximately $700 million per year and $8 billion over the next decade. [10] This cost is shared between DoD and NNSA. [11]

NATO nations that host U.S. nuclear weapons bear many of the costs associated with the weapons. In addition to providing and maintaining aircraft and personnel, host nations are responsible for maintaining the facilities and infrastructure associated with forward-deployed nuclear weapons. These costs are difficult to estimate since they are paid out of national budgets. In addition to host nation support, NATO has collectively invested over $80 million to improve security for nuclear weapons since 2000. [12] NATO currently plans to invest an additional $154 million “to meet with stringent new U.S. standards.” [13]

As the existing stockpile of B61 bombs approaches retirement, NNSA and DoD are planning a life extension program for the B61 estimated to cost approximately $8.2 billion in FY2016 (in addition to the B61s deployed in Europe, the Air Force also maintains a smaller number in the United States for use by the B-2 bomber). [14] The Life Extension Program (LEP) is designed to replace or refurbish nuclear and non-nuclear components of each B61 in order to ensure their safety and reliability while minimizing the need to design or test new components. [15]

The Air Force is working on a program to equip the refurbished B61s with a new maneuverable tail that will significantly improve their accuracy, and enable them to be used against targets that would otherwise require bombs with more destructive power and higher yields. Total cost estimates for the project had ballooned from an initial estimate of about $4 billion to about $8.9 billion as of September 2015. [16]

5. What other Defense Department programs are essential to maintaining the U.S. nuclear triad, and what are their costs?

In addition to the delivery systems themselves, other programs are essential to maintaining a safe, effective, and reliable nuclear arsenal.

- Command, control, and communications systems ensure that nuclear weapons can be used when authorized by the president and—just as importantly—that they cannot be used without proper authorization. DoD uses multiple redundant systems to ensure connectivity before, during, and after the use of nuclear weapons. Early-warning radars and heat-sensing satellites constantly scan the skies looking for signs of an attack by a bomber or missile. The CBO estimates these systems cost $5.2 billion a year and will cost $52 billion over the next ten years. [17]

Left to right: 1. Early Warning radar in Alaska, source: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. 2. Space Tracking and Surveillance System, source: U.S. Air Force.

- The intelligence community supports the nuclear mission by obtaining strategic intelligence about an adversary’s military capabilities and intentions, acquiring targeting data for nuclear strikes, performing background checks on personnel who need access to classified information pertaining to nuclear weapons, and maintaining the codes used to authorize a nuclear attack. These costs are classified, and few credible estimates exist in the public domain.

- DoD also has a continuity of operations program, with a secure backup facility outside of Washington, D.C. to ensure it can function during or after a nuclear attack or an incidence of nuclear terrorism. This program is highly classified, and its full costs are unknown, but are estimated to be at least several hundred million dollars per year. [18]

Sources

[1] Congressional Budget Office, Projected Costs of U.S. Nuclear Forces, 2014 to 2023, (Washington, DC: December 2013).

[2] “Arms Control NOW,” Last Obama Budget Goes for Broke on Nuclear Weapons, accessed July 14, 2016. https://www.armscontrol.org/blog/ArmsControlNow/2016-02-09/Last-Obama-Budget-Goes-for-Broke-on-Nuclear-Weapons

[3] “Projected Costs of Nuclear Forces 2015-2024,” Congressional Budget Office, accessed July 14, 2016. https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/114th-congress-2015-2016/reports/49870-NuclearForces.pdf

[4] Harrison, Todd, “Defense Modernization Plans through the 2020’s Addressing the Bow Wave,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, January 3-5, 2016. http://csis.org/files/publication/160126_Harrison_DefenseModernization_Web.pdf

[5] Jon B. Wolfsthal, Jeffrey Lewis, and Marc Quint, The Trillion Dollar Triad, (Monterey, CA: James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, January 2014).

[6] In FY16 dollars. This number includes extrapolated future operations and maintenance costs between the systems’ introduction and 2040. Jon B. Wolfsthal, Jeffrey Lewis, and Marc Quint, The Trillion Dollar Triad, (Monterey, CA: James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, January 2014).

[7] In FY16 dollars. The Air Force estimates that the program will cost $62.3 billion, the figure of $70.4 billion includes estimated operations and maintenance costs between the missile’s introduction and 2040. Reif, Kingston, “Air Force Drafts Plan for Follow-On ICBM,” Arms Control Association, July 8, 2015. https://www.armscontrol.org/ACT/2015_0708/News/Air-Force-Drafts-Plan-for-Follow-on-ICBM

[8] Hans M. Kristensen and Robert S. Norris, “US Nuclear Forces, 2014,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Vol. 70, No. 1, p. 92.

[9] Hans M. Kristensen, “Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons,” Federation of American Scientists, Special Report No. 3, May 2012, p. 52, www.fas.org.

[10] The CBO annual vs. ten-year estimates appear to be inconsistent because of rounding decisions. These are the numbers CBO reported. Congressional Budget Office, Projected Costs of U.S. Nuclear Forces, 2015 to 2024, (Washington, DC: January 2015), p. 4.

[11] Congressional Budget Office, Projected Costs of U.S. Nuclear Forces, 2015 to 2024, (Washington, DC: January 2015), p. 4.

[12] “NATO Nuclear Weapons Security Costs Expected to Double – Federation of American Scientists,” Federation of American Scientists, accessed July 14, 2016. https://fas.org/blogs/security/2014/03/nato-nuclear-costs/

[13] “NATO Nuclear Weapons Security Costs Expected to Double – Federation of American Scientists,” Federation of American Scientists, accessed July 14, 2016. https://fas.org/blogs/security/2014/03/nato-nuclear-costs/

[14] “All Things Nuclear,” All Things Nuclear, accessed July 15, 2016. http://allthingsnuclear.org/emacdonald/nnsas-roller-coaster-ride-on-costs-of-the-32-plan

[15] “NNSA, Air Force Complete Successful B61-12 Life Extension Program Development Flight Test at Tonopah Test Range,” National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), accessed July 15, 2016.

[16] “Nuclear Weapons: NNSA Has a New Approach to Managing the B61-12 Life Extension, but a Constrained Schedule and Other Risks Remain,” Government Accounting Office, February 2016, pp 6-7. http://www.gao.gov/assets/680/674960.pdf

[17] Congressional Budget Office, Projected Costs of U.S. Nuclear Forces, 2015 to 2024, (Washington, DC: January 2015), pp. 4, 7.

[18] Stephen I. Schwartz and Deepti Choubey, Nuclear Security Spending: Assessing Costs, Examining Priorities (Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2009), p. 36.

Chart Sources

[1] 2015 Operating Costs for the Triad: The CBO annual vs. ten-year estimates only appear to be inconsistent because of rounding decisions. These are the numbers CBO reported. Congressional Budget Office, Projected Costs of U.S. Nuclear Forces, 2015 to 2024, (Washington, DC: January 2015), p.4.

[2] Long-Term Nuclear Triad Costs: These costs are based on the following sources, modified to include extrapolated operations and maintenance (ONM) costs out to 2040, derived from The Trillion Dollar Triad.

For the Minuteman Follow-on: Kingston Reif, “Air Force Drafts Plan for Follow-On ICBM,” Arms Control Association, July 8, 2015, www.armscontrol.org.

For the Minuteman III ICBM: Jon Wolfsthal, Jeffrey Lewis, and Marc Quint, The Trillion Dollar Triad (Monterey, CA: James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, January 2014), p 23.

For the Ohio-class SSBN: The Trillion Dollar Triad, p 15.

For the SSBN (X): The Trillion Dollar Triad, p 14.

For the ALCM: “Air-Launched Cruise Missile (AGM-86B),” Brookings Institution, www.brookings.edu

For the LRSO: The Trillion Dollar Triad, p 11.

For current strategic bombers: The Trillion Dollar Triad, pp 18-19.

For the B-21: Lara Seligman, “McCain Demands Air Force Release B-21 Bomber Contract Value,” Defense News, March 16, 2016, www.defensenews.com

Photo credit

Header Image: The Nuclear Triad is a combination of nuclear forces by land, air and sea. Sources: All header images are from WikiMedia Commons.